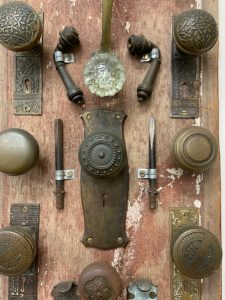

Today, the faded red barn boards are dusty. Embossed escutcheons appear a little rusty. Aged glass doorknobs gleam in golden and amber hues.

|  |  |

A.O. (Andy) Anderson, Cortney’s paternal grandfather, collected antique glass doorknobs, and other heirloom door hardware. He artistically mounted locks, hinges, handles, keys and more, on weathered wood panels salvaged from her maternal grandfather’s Tipton, Iowa, farm. The historic hardware decorates a wall in our Main Office showroom.

|  |  |

“Early Locks and Lockmakers of America,” a limited edition book compiled by Thomas F. Hennessy, in 1976, notes a patent issued to the Eagle Lock Company, on November 4, 1826, for a “Glass Door Knob” invented by Whitney & Robinson.” This marked the beginning of a decorative door hardware boom. Glass is mostly made of sand, which is not only abundantly available, but which melts and becomes beautifully transparent when heated at extremely high temperatures.

Artisans poured glass, in its liquid state, into molds to form doorknobs. Pressed and machine-cut glass knobs came in familiar round and egg shapes, as well as hexagonal and other faceted designs. Various shapes were molded into the bases, like the precisely incised star patterns in the glass knobs illustrating this blog. Escutcheons, the ornamental backplates around the door handles, from this period are similarly ornate.

Artisans poured glass, in its liquid state, into molds to form doorknobs. Pressed and machine-cut glass knobs came in familiar round and egg shapes, as well as hexagonal and other faceted designs. Various shapes were molded into the bases, like the precisely incised star patterns in the glass knobs illustrating this blog. Escutcheons, the ornamental backplates around the door handles, from this period are similarly ornate.

From 1830-1873 over a hundred U.S. patents were granted for knobs. However, mass production of glass doorknobs didn’t start until 1917. By the 1920’s, the largest hardware makers, such as Yale & Towne Manufacturing Company, were mass-producing doorknobs from sand.

Cut glass doorknobs featured 12, 8 or 6 facets, or faces, looking like large diamonds. The crystal from that time had a watery appearance, unlike today’s clear materials, related to differences in manufacturing methods.

Cast metal knobs were introduced in 1846. The new century saw brass, bronze and iron knobs opening doors in new homes across America. But glass and porcelain knobs returned to popularity during the Depression, as they were made from cheaper materials; and again, during war years when metal was conserved for military uses.

A hallmark of crystal door knobs manufactured before 1900 is a spindle without threads, secured with small screws, with holes at each end through which a rod was inserted. In later years, knobs had square threaded shanks fit inside square spindle door hardware.

Sparkling crystal knobs, from mid-1900’s, are durable, easily maintained, and reasonably priced. Their fine craftsmanship, solid brass shanks, and the adaptability to work with modern locksets makes them desirable by owners of restoration, as well as new, houses. Glass knob designs range from vintage Victorian to simple mission styles.

Look at the metal to identify the difference between reproduction crystal door knobs and antique ones. The popularity of these products led to more companies designing their own lines of glass door knobs and introducing shapes, such as octagon, oval and ball.

Glass doorknobs may mimic antique designs, but metal back plates have changed greatly. Different manufacturers use different threading so parts can’t be interchanged.

|  |  |

Today’s glass doorknobs, crafted from lead crystal, can be easily distinguished from vintage crystal doorknobs. Manufacturers such as Emtek and Schlage have updated antique style knob sets that fit any décor. Their sharpness and clarity adds elegance to any home.

Cabinet hardware can be easily upgraded with decorative crystal knobs.

Crystal, or glass, doorknobs are mainly specified for non-keyed passage or privacy functions. Hallway and closet doors that latch, not lock, for example, are “passage function.” Bedroom and bathroom doors, which can be locked with the addition of a pushbutton on the escutcheon, or backplate, and unlocked, in case of emergency, by inserting a sharp object into the hole on the outside of the escutcheon, are designated “privacy function.”

An interesting caveat I learned while researching this blog is that typically benign crystal doorknobs can start a fire! They act like magnifying glasses when direct sunlight passes through them.